Author: Liz Poppert DPT, MS, OCS

Is your patient “Fit to Run” or is she “Running to be Fit”? How can a physiotherapist help recreational runners recover from and train to prevent future injuries?

Consider the statistics: 19-92% of runners are injured yearly(1,2). These statistics vary based upon the definition of a running injury and the definitions include: Pain or symptoms during or immediately after running, onset of pain or symptoms coinciding with the beginning of a running program, pain or symptoms significant enough to force abandoning running or reducing the volume of training(3).

Numerous authors have outlined risk factors for future running injuries by surveying and examining factors associated with history of running injuries. Some of these risk factors can be controlled, for example body mass index, weekly training frequency and distance, recovery time, fitness, and footwear. Others are not controllable and include, for example, age and skeletal alignment. Across all epidemiological reports, the most common risk factor for the risk of a running related injury is a history of a prior running injury(2,4,5,6).

Now consider the physical capacity demands of this sport: Running involves High, Rapid, and Repetitive force attenuation and production. The overwhelming majority of the power supplied by the hip, knee and ankle while yielding then propelling itself from the ground is performed by the hip (39%), knee (42%) and ankle (19%) at an 11.7km/hr pace (7). Not surprisingly roughly 78% of running injuries occur at the knee or below. The peak ground reaction forces acting on the body result in high loads and approach 3-times body weight with each step compared to 1.45-times body weight during fast walking(8). This load, is rapidly applied as the runner’s foot contacts the ground and yields to absorb the ground’s forces on the body. The knee joint for example moves at a rate of 264 degrees/second and ankle joint moves at a rate of 688 degrees/second (9) Both the magnitude of forces and the rate of force application are associated with injury risk. Add on to that, the repetitive nature of the process of force absorption and production during each landing and propulsion cycle for every foot strike. Each leg subject to this mechanical stress close to 90 times per minute. That amounts to nearly 2500 times on a 5k run!

How does the typical recreational runner train to build the capacity to meet these demands? Mostly by running.

Runners run to get fit but are they fit to run?

Given the startling statistics on running related injuries and an appreciation for the physical demands of running a new perspective is required.

While running improves fitness…it demands fitness!…..ALL aspects of fitness!!

Typically running is viewed as an aerobic activity, a “long slow distance” activity. This is not incorrect, but there is more to it. The fit runner possesses all attributes of physical fitnessincluding: aerobic and anaerobic metabolic capacity, lower extremity and trunk neuromuscular performance, lower extremity and trunk muscular, strength and endurance, lower extremity power, balance, and flexibility.

The physiotherapist will evaluate the runner and seek to answer the question: “Is my patient fit to run?” Assessment of the injured runner begins with a needs analysis to in order to appreciate the runner as an individual athlete. The runners history, including medical, running and fitness history is carefully reviewed in the context of the presenting injury and the runner’s personal motivation and goals. The physiotherapist derives clues from the history which guide selection of and athlete specific objective examination. This includes running skill analysis, fitness testing and an injury/region specific orthopedic examination.

Skill assessment:

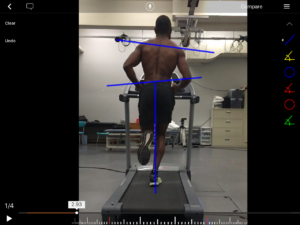

Until recently, scientific assessment of the running gait was limited to the laboratory setting, either at universities or elite and professional sports training centers. Now, thanks to the availability of slow motion video on the basic tablet or smart phone, physiotherapists can evaluate the running gait in their clinics. Using these 2-dimensional images the physiotherapist can analyze specific phases of the running gait cycle and identify movement patterns and postures that are associated with aberrant and potentially injurious forces onthe runner(10,11,12).

Physical capacity assessment:

The running and fitness history in addition to the running skill analysis can highlight gaps in training and performance that provide insight into the runner’s injury. These findings help drive the selection of physical fitness tests for specific to each runner (13,14). For example, to assess for trunk muscle endurance a side bridge (photo above) hold for time may be selected. This and other tests of trunk muscle endurance, strength and control were found to be limited in track athletes with lower extremity injury compared to healthy teammates (15). The Star Excursion Balance Test (photo in the middle) can identify impairments in dynamic stability associated with running demands, can predict risk of lower extremity injury and becomes an exercise intervention for patients with running injuries (16). The triple hop test (photo below) is used to assess side to side power deficits in the runner and provides an excellent qualitative view of lower extremity loading and propulsion (17).

Orthopedic assessment:

By combining the skill and physical capacity assessment the physiotherapist can hone in on the pathoanatomical injury by performing a region specific orthopedic examination.For example, joint alignment and mobility (photo above), joint tenderness (photo in the middle) and pain provocation, and isolated muscle length tests (photo below).

In summary, appreciation of the physical demands of running and the runner’s history,motivation, skill, and capacity combined with the running specific orthopedic assessment will allow the physiotherapist to hone in on the runner’s problem and customize a treatment and training plan that will enable the runner to Run Well and Perform Well!

Liz Poppert DPT, MS, OCS blends academics, as an Adjunct Assistant Professor of Clinical Physical Therapy at the University of Southern California, and clinical work at her Santa Monica,California private practice. Her teaching and publications aim to educate practitioners to apply best evidence, biomechanics and principles therapeutic exercise to maximize patient outcomes with rehabilitative exercise programs especially for individuals with low back pain and running related injuries. Dr. Poppert is a member of the APTA Running Special Interest Group, is certified as an ACSM Exercise Physiologist and United States Track and Field Level One Coach. She is avid recreational runner and enjoys training and competing with the Track Club of Los Angeles.

Liz Poppert DPT, MS, OCS blends academics, as an Adjunct Assistant Professor of Clinical Physical Therapy at the University of Southern California, and clinical work at her Santa Monica,California private practice. Her teaching and publications aim to educate practitioners to apply best evidence, biomechanics and principles therapeutic exercise to maximize patient outcomes with rehabilitative exercise programs especially for individuals with low back pain and running related injuries. Dr. Poppert is a member of the APTA Running Special Interest Group, is certified as an ACSM Exercise Physiologist and United States Track and Field Level One Coach. She is avid recreational runner and enjoys training and competing with the Track Club of Los Angeles.

References:

- Saragiotto BT et al. (2014) What are the main risk factors for running related injuries. Sports Med; 44:1153-1163.

- VanGent RN et al. (2007) Incidence and determinants of lower extremity running injuries in long distance runners: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med; 41:469-480.

- Taunton JE et al. (2002)A retrospective case-control analysis of 2002 running injuries.Br J Sports Med; 36:95-101.

- Macera CA. (1992) Lower extremity injuries in runners. Sports Med; 13:50-57.

- Ryan MB et al. (2006) A review of anthropometric, biomechanical, neuromuscular and training related factors associated with injury in runners. Int J Sports Med;7:120-137.

- Taunton JE et al. (2003)A prospective study of running injuries: the Vancouver Sun Run “In Training” clinics. Br J Sports Med; 37:239-244.

- Ferris DJ and Sawicki GS. (2011) The mechanics and energetics of human walking and running: a joint level perspective. J R Soc Interface;9: 110-118.

- Whittle M.(1996) Gait analysis: An introduction, 2nd Ed. Oxford Butterworth-Heinemann Ltd.

- Belli A et al. (2002) Moment and power of the lower limb joints in running. Int J Sports Med; 23:136-141.

- Pipkin J et al. (2016)Reliability of a qualitative video analysis for running. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther; 46:556-561.

- Souza RB. (2016) An Evidence-Based Videotaped Running Biomechanics Analysis. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics of North Americ.;27:217-236.

- Wille CM, et al. (2014) Ability of sagittal kinematic variables to estimate ground reaction forces and joint kinetics in running. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther;44:825-830.

- Sinnett AM, et al. (2001) The relationship between field tests of anaerobic power and 10k run performance. J Strength and Conditioning Research;15:405-412.

- Plastaras CT et al.(2005) Comprehensive functional evaluation of the injured runner. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am; 15:623-649.

- Gribble PA et al. (2012) Using the* excursion balance test to assess dynamic pastoral – control deficits and outcomes in lower extremity injury: a literature and systematic review. J Athletic Training;47:339-357.

- De Blaiser C et al.(2018) Is core stability a risk factor for lower extremity injuries in an athletic population? A systematic review. Phys Ther in Sport; 30:48-56.

- Hudgins, B et al. (2013) Relationship between jumping ability and running performance in events of varying distance. J of Strength and Cond Res;27:563-567.